Thursday, December 24, 2015

Toward the end of the 80s, I was becoming increasingly disgruntled with what I perceived as the lack of new ideas and energy in jazz. Having cut my teeth, since 1972 or so, on the AACM, JCOA and offshoots and other amazing individuals and organizations, I was hearing a kind of stultification setting in, a complacency of sorts. Sure there were still the occasional bursts of excitement and creativity--I still think of Anthony Braxton's notion to have his quartet interpolate entirely other compositions at will to be the last "great" idea in jazz--but more and more it seemed that musicians were treading water. The raw creativity heard in, say, Roscoe Mitchell in 1968, seemed to be a thing of the past. I cast around, of course, finding temporary solace in the burgeoning downtown New York City scene, whose sizzle pretty much evaporated within a decade (and scarce little of which I can return to these days without grimacing) but was always on the lookout for solution to the dilemma I perceived. For a while one such might have been the combination of solid, Mingusian themes and arrangements with free soloing and more expansive structures. I'd been a big fan of the Willem Breuker Kollektief since seeing them several times at Environ in 1977 or '78 but by 1985, their shtick had begun to wear very thin. Bands led by Henry Threadgill, Olu Dara and, to a lesser extent, David Murray made things click for a few years but those too eventually succumbed to a kind of laurel-resting torpor (though, of course, many would disagree).

I'm guessing it was in the review section of Cadence or possibly Coda that I first came across the mention of Simon H. Fell and, if I'm remembering correctly, those write-ups cited Fell's use of robust structures (Mingus' name was certainly invoked) integrated with aspects of free playing from the European school, another area I'd begun reinvestigating since more or less abandoning it in the mid-70s in favor of AACM and other American jazz avant approaches. It seemed to me a possible source of new and exciting work so, around 1986, I ordered Fell's Compilation I on the Bruce's Fingers label (I'd get Compilation II a few years later). I've long since given away almost all of my vinyl and no one's seen fit to upload music from either of these recordings as near as I can tell, so I can't say with any exactitude but recollect that I was hot and cold on the recordings, enjoying some portions the more robust and bluesier it got, finding other parts too cleanly abstract (in the "standard" British free-improvising sense), a bit oil and water, though overall my response was positive (see All Music reviews here and here). His band, Persuasion A and their release, "Two Steps to Easier Breathing" (1988) struck me as much more successful, ably drawing on South African musical traditions. Things were quiet on the Fell front until the late 90s when my friend and Cadence critic Walter Horn wouldn't stop proselytizing about "Composition no. 30" (1998, also on Bruce's Fingers), a 2-CD set for a big band of some thirty musicians (including several whose work I would devour in upcoming years, like Mark Wastell, Rhodri Davies and John Butcher). Once again, my reaction was mixed, enjoying some parts while finding others overly arid, though I began to get the sense that this was precisely what Fell was after and that, simply put, his aesthetic interests were somewhat different than my own, especially as I grew more and more disenchanted with new jazz, and so it went.

My next encounters with Fell came from a very different direction, however. I forget which arrived first but in any case, they were in the forms of IST (with Davies and Wastell, also the sole context in which I've seen Fell perform live, at Tonic in the early oughts; more on that below) and VHF (with Graham Halliwell and Simon Vincent) on the very first recording issued by Erstwhile in 1999. Along with groups like Polwechsel and Sugimoto's "Opposite", VHF was very significant for me, gradually laying open the world of "quiet improv"; I recall spending many an hour listening to it, listening in a different way than I had before, unpeeling translucent layers on each go-round. IST was slightly different, still having half a foot in the efi tradition; I'd love to hear that Tonic show again, curious if there was a divide between the harp and cello and Fell's bass. I was sitting directly in front of Fell and he put on a mighty performance--I found myself worrying several times that he might injure himself, including when he stuck the fingers of one hand under the bass strings and bowed atop both and when, his hands otherwise occupied, he used his left ear, rather forcefully, to depress strings on the fingerboard.

In the intervening years, I've only come across Fell's work sporadically, most recently in a pure improv context on Confront releases of older material with Derek Bailey and IST. Receiving the disc in question today brought back all of the above memories and having shortly thereafter serendipitously met Fell in Huddersfield and engaged in an all too brief conversation, I was intrigued to hear the latest in his compositional series, No. 79, "The Ragging of Time". And, dammit, I find myself having the same issues...

Some context. The work was presented as part of the Marsden Jazz Festival of 2014 and some thought was apparently given to commemorating the onset of World War I. I take it that John Quall, the festival's producer, more or less commissioned the piece, understanding that the date was roughly contemporaneous with the first jazz recordings and that Fell would incorporate thematic material from the time with contemporary sounds, restoring "the birthright of early jazz to make those traditional sounds new, to make them shocking, to make them the 'Devil's music' as it was once before." A tall order, indeed, but one that could, as far as I could glean from those 80s-90s recording of Fell's, fit comfortably into the structures established back then. Fell assembled a very strong sextet whose instrumentation referred to common ensembles of the era (Percy Pursglove, trumpet; Alex Ward, clarinet; Shabaka Hutchings, bass clarinet; Richard Comte, guitar; Fell, double bass; Paul Hession, drum set) and had at it.

The work is in three sections and the band immediately launches into a Morton-esque theme, bouncy and reasonably convincing, before quickly veering into a free improvisation featuring some blistering clarinet work from Ward. In microcosm, this is the model in use throughout: areas of thematic material interlaced or overlaid with a fairly aggressive but not atypical (within efi) improvised section, sometimes with written lines traced in the background, recalling (for me) a strategy used by Braxton among others. Different attacks and groupings are apparently scored with exactitude as the shifts within a given section are crisp and finely contrasting. All of the playing is first rate, especially Ward and Hutchings (the latter a name new to me) and I guess if you listen to the music from a post-Bailey, etc. point of view, you'll be well satisfied. I find it impossible to ignore the framing, however, and wonder about the reasons (aside from its seeming commissioned origins) to construct things this way. I mentioned the Breuker Kollektief above and there's something similar in structure here (albeit without the goofy humor and typically isolated solo turns, though the latter appears once or twice). As said, I have an affinity for much of that work up to a point, but that point was reached in the mid-80s and is difficult for me to regenerate enthusiasm thirty years on even if allowing for the fact--and I think this is decidedly the case--that Fell's group is more serious and committed. I think I would have far preferred it had no overt references to early jazz been made, instead touching on the matter more obliquely as occurs in the lovely three horn section toward the end of part one. On the other hand, the themes themselves, especially that from the second "movement", are extremely attractive and tastily arranged, as is a lovely secondary theme introduced about halfway through. It's simply something about the juxtaposition that bothers me, that oil and water thing. Shocking? No, not at all, just not integrated in a way I found engaging.

But still...as much as this general language isn't something I'm too keen on nowadays and as much as I have issues with the (to me) forced confluence of styles, there's a decent portion of music that's simply exciting, even thrilling (for example a section beginning some five minutes into the third track). It is reminiscent of past musics, though these connections are likely more on my part than Fell's. I pick up a bit of John Carter now and then, for example, not a bad point of reference at all. And to be sure, those listeners with less of a bone to pick with this school of free improv will (and should) ignore my quibbles entirely and dig in; they'll have a great time and experience work at a very high level.

(While writing this piece, I found a wonderful video of Fell playing solo. There's an enormous amount of subtlety and beauty going on here. It's more in accord with where my focus is these days and has me hoping that, at least, he one day creates a bridge of sorts between this approach and his ensemble work. Perhaps he has and I'm simply ignorant of it.)

Bruce's Fingers

Sunday, December 20, 2015

Jürg Frey - string quartet no. 3/unhörbare zeit (Edition Wandelweiser)

What to say? Two works, Frey's third string quartet (2010-2014) and a piece for string quartet and two percussionists (2004-2006), with Quatuor Bozzini on each, assisted by Lee Ferguson and Christian Smith on the latter.

I get the impression that if you half-listened to the string quartet, you might get the impression of stasis and self-similarity though nothing could be further from the truth. In his notes, Frey compares it to "the silence of a square, a room, a wall or a landscape" and that gets to the heart of the matter--one merely has to listen the way one can simply and deeply observe a wall to perceive not just the variations but the progressions, the story even. Recent releases from Frey have varied between the surprising melodic lushness heard on the Musiques Suisses recording and the grayer, more austere approach heard on "Grizzana" (Another Timbre), both of which I love deeply. The two works here strike me as somewhere between; more accurately, ranging from one boundary to another, and much else besides.

The string quartet is deceptive. On my first listen to the disc, it was "unhörbare zeit" that grabbed me but upon repeated listenings, it was clear how much I was missing in this piece. It begins with single whole note chords, grainy and exquisite, separated by a brief rest, in a calm sequence that has a little bit of a back and forth quality. After three minutes, the single notes separate into pairs, retaining the initial serenity. Back to single notes for a short time, then back to pairs, the tones acquiring a more worried and tense quality though the pacing remains the same. It subtly shifts into groups of four chords some 6 1/2 minutes in, sadder now. The emotional tinges throughout are always changing. Frey may object, but I hear a kind of narrative thread, finding myself in the mind of someone taking a long, quiet walk, perhaps remembering a friend recently lost, the highs and lows. This is encouraged by the fact that one hears (especially when listening on headphones) the breathing of some of the musicians as well as other non-instrumental sounds. Whether intentional or not, it acts to personalize the setting quite beautifully. The chords are attenuated, thinned to whispery lines, almost weeping, their sequencing becoming sparser, the spaces between lines lengthening a bit, before richer tonalities emerge. About halfway in, the mood becomes languorous and, dare I say, hopeful. The comparison may not be apposite, but I found myself thinking that this is the kind of music that, a few decades back, I hoped Gavin Bryars would write. But this is more profound, lush while retaining the requisite trace of bitterness. In the meantime, the pacing, while never disappearing, has become more blurred--there are many things happening throughout and I hear different aspects each time I listen. The music becomes more hushed, still richer and deeply grained, but barely stirring, longish lines wafting one by one through the air in the room like breath in the cold. In the end, the "walk" resumes, with more a sense of the inevitableness of loss combined with moving onward. A stunning, truly moving work, my favorite piece of composed music in quite a while.

Which is not to slight "unhörbare zeit", which is sumptuous as well and, indeed, in some ways is not so dissimilar. The added percussion provides a fertile layer of sound, hear dark and rumbling there softly jangling. Again, the pacing is calm and steady, individual "blocks" of sound looming into audibility, evanescing. If I can extend or at least refer to the imagery the first piece conjured in my head, understanding that I may be imputing too much, one difference might be that this work is more purely sound-concerned and less emotionally suffused. Still, the somberness of, say, the heavy but hollow, low percussion blows, sounding singly against string bowing that as become less regular, more fragmented, carries a dark intensity of its own. The world is bleaker, more concerned with the immediate environment than memories. There's some amazing music herein, though, including a set of chords late in the piece that sound for all the world like accordions, baffling me and lending a slightly queasy air to the conclusion of the work, very unsettling and effective.

Fantastic music, in any case. For anyone at all partial to Frey's work, it's an automatic. Personally, it's my favorite recording of composed music heard in 2015, possibly for longer than that.

Edition Wandelweiser

Also available from Erst Dist

Friday, December 04, 2015

Devin DiSanto/Nick Hoffman - Three Exercises (ErstAEU)

In a previous post, I mentioned the group of sets heard at AMPLIFY:exploratory that, as a whole, I found more interesting in approach, all of which involved Graham Lambkin and Taku Unami. Unami, here and in his 2011 visit, seems to come prepared with one basic idea which he iterates during all or most of the sets in which he's involved. This time it was fans, floor level and standing, employed both for the movement and noises they created on their own (sometimes interacting with each other) and their effect on garbage bags and the occasional small cardboard box. He also engaged in a little bit of surprising but very apt piano playing as well as wielding an electronic device or two. The festival opened with Unami and Sean Meehan, the latter playing (I think--he was seated on the floor and my view was entirely blocked) a set of bells. It was lovely and very quiet, the fans whirring softly, sometimes, by virtue of their rotational abilities, jangling against each other, blowing the green/black bags in a hushed rustle. There was plenty of silence and, several times, this was broken by an unexpectedly brilliant bell cascade. Really nice, made me want to hear a festival in which Meehan played in every set. But it also signaled that "other" path, the one more oriented on actions than musicality. In some ways, this dichotomy was expressed at its most extreme within the confines of a single set later that evening with Lambkin and Michael Pisaro, who more or less reproduced the ambience from their prior release on Erstwhile, "Schwarze Riesenfalter", Pisaro possibly playing some of the same piano chords heard therein, I'm not certain. Lambkin, however, apparently under the influence of sundry substances, delivered a performance that was in some ways truly dangerous; he seemed to walk a thin line between control and recklessness (but always, as ever, deeply and oddly musical!), breaking a glass candle here, toppling a mic stand there, threatening to lift a massive speaker and do who knows what. Pisaro, calm as ever, negotiated these events wonderfully, incorporating them into the overall structure even while being wrestled bodily. It was a thrilling set, at least partially because of the utter lack of predictability involved.

I confess, writing more than a month later, that I've forgotten most of the details of the Lambkin/Unami collaboration. There were fans and bags, of course, as well as more piano from Unami. Lambkin was in greater control. I have an odd sense of enjoyment though, for the life of me, I can't recall specifics! Ah well....

Unami played three sets during the festival, his final with Devin DiSanto. The bulk of the idea seems to me to have been DiSanto's (implicitly borne out by his activity on the "Three Exercises" recording) with Unami adding "commentary", but I could be wrong. In any case, it resulted in perhaps my favorite set of the weekend. DiSanto was seated at a table with a monitor and other equipment, the image from the monitor's screen projected on the wall behind him. Unami sat crouched in a corner delivering electronic sounds that conveyed a vaguely Japanese science fiction film feeling, an interesting tinge but not distracting from the action center stage. There, DiSanto, his chiseled face, slicked back hair and white shirt buttoned to the collar inevitably evoking Kyle McLachlan and thereby imbuing the affair with Lynchian overtones, engaged in a Personal Assessment test. I'm guessing from his demeanor that despite knowing the general parameters of the test, he wasn't aware of the specific questions. In any event, he pretty much maintained a straightforward, non-overtly ironic approach, patiently answering questions to the extent he could (there was an "Uncertain" button which was pushed once in a while, rather amusingly). It was funny, sure, but I had the impression that DiSanto has a deep fascination with these kind of tests, with their tenuous association with reality, etc. I found it absorbing to experience as well as a bit uncomfortable in the invasion-of-privacy sense. Granted that there are many precedents for this kind of performance activity, from Fluxus and beyond, but still it's rare enough in my experience to remain stimulating and thought-provoking.

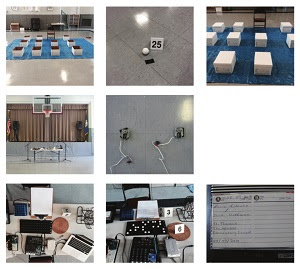

While I assume that the contributions of DiSanto and Hoffman to the recording in question were more or less equal, the cover photos indicate a situation that has the former's name written all over it. In fact, it cries out for a video so one can get an idea of what's occurring. Nonetheless, my favorite aspect of it is the sheer immediacy one feels, of being palpably inside this room, this school gymnasium (?) while all the baffling activity is taking place. It seems to be presented quite matter-of-factly, from beginning to end though I wouldn't be surprised if there was a decent amount of post-production collaging (as with the Parks/Rossetto release, all credit due to Joe Panzner's mastering). It begins ("preparation/introduction") with several minutes of the sounds of the room, various clicks and bangs as things are placed on tables or floors, the people involved are shuffling around, talking, tape is being pulled, etc. Very transparent and mysterious at the same time. The piece is indeed introduced and commences with a short roar. Throughout, there are interjections like this, sequences of a more "musical" nature but the bulk of the recording isn't so far from it's first section, except that instead of preparing the field, certain designated activities are taking place within it. One senses a kind of system, opaque as it is. DiSanto saying, "...paper. Two: deer. Three: pier. Four: read." (or "dear", "peer", "reed"?), talk of placing numbers near ping pong balls and what sounds like an excerpt from a Bingo game all speak to processes ranging from arcane to banal. Descriptions of activity are heard, subdued and grainy, by male and female voices. Whatever the process is, it's always apparent, a strong sense of steps being taken. Sonically, it's like a hyper-concentrated Ferrari piece, relaxed and seemingly "true" but suffused with purpose. It sounds pretty spectacular, which at the end of the day, is enough. On second thought, I'd probably rather not see a video, preferring to conjure up my own images and explanations.

Fine work and exemplary of the kind of approach I found so invigorating at the festival.

Erstwhile

Wednesday, December 02, 2015

Some thoughts on this past weekend at the 2015 Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, seven concerts and two talks from memory, no notes taken).

Arriving in Manchester early Friday morning we were quickly and almost efficiently whisked Huddesfield-ward by the indomitable Richard Pinnell, admiring the Pennines on our way. We made it in plenty of time for the noon concert: Ensemble Grizzana playing four pieces by Jürg Frey, from his album, "Grizzana" on Another Timbre. The performers were Frey (clarinet), Mira Benjamin (violin), Richard Craig (flute), Emma Richards (viola), Philip Thomas (piano) and Anton Lukoszevieze (cello). I can't locate any etymological information on the name, but when I hear "Grizzana" I think of "grisaille", helped along by the sublimely beautiful grayness of Frey's music. The first two, "Fragile Balance" and "Grizzana" were with the complete sextet, very quiet and delicate, grainy. This was the first time I'd actually seen Frey perform (or, I think, heard any live music of his?) and, apart from the airy beauty of his conceptions, his clarinet playing was extraordinary; such control combined with calm emotion. As lovely as those pieces were, when only the piano, cello and clarinet remained for "Area of Three", a 30-minute work, something immediately clarified and the atmosphere became more crisp as the instruments entered in that order, creating great tension and concentrated precision. Even so, my favorite was "Ferne Farben", the full sextet augmented by a super-subtle tape of field recordings, the instrumentalists adding "simple" tones within certain time parameters but leaving much to their discretion (I think). In any case, a stunning work.

I'd had less than two hours of sleep in the previous 48, so I reluctantly begged off attending a set of three films by Huw Whal revolving around AMM performances and one done by Philippe Regniez in 1986 about Cardew which subsequently received good word of mouth. I did rouse myself, however, to see an interview of Eddie Prévost by Philip Clark. As an interview, it was rather disappointing, either dwelling on anecdotes that most AMM aficionados are likely to have already known or beginning to delve into interesting questions but never quite getting there. However, I was pleased to see Prévost in apparent good humor, an impression solidified over coffee and dinner prior to the next show. He was nothing but warm, funny and generous all weekend, quelling any fears I may have had about the upcoming "reunion" set. Dinner also precluded the possibility of hearing George Lewis' collaboration with the Berlin Splitter Orchestra though reports were middling, sounding like something along conduction lines.

That night, the wonderfully sensitive Philip Thomas presented three more compositions by Frey (all of which appear on the new Another Timbre release, "Circles and Landscapes"), his final showing of the festival, where he'd been composer-in-residence all week. The relatively brief (about five minutes long) "Extended Circular Music No. 2" (2014) was up first, a darkish work with troubling chords that makes me think of a slow-motion, downward stumble--absolutely fantastic. This was followed by two longer, far more "difficult" pieces, "Pianist, Alone (2)" (2010/2012) and "Extended Circular Music No. 9" (2014/2015). My immediate frame of reference was Satie's music from the Rosicrucian period, things like the "Ogives" with their impressive steady sparseness. Speaking with Frey afterward, he said that while many of his compositions tended to "stay in one place", he had become interested in works that progressed, went from here to there and there's certainly a kind of processional feeling at play, exceedingly serene in forward motion if delightfully unsteady in tonal content. Their length (about 30 and 22 minutes respectively) makes it difficult, for me at least, to really grasp as a whole, but I found them quite mesmerizing and listening right now to the above-mentioned CD--well, it's pretty incredible music. A special joy over the course of the festival was hearing Thomas for the first time--quite a wonderful and sensitive player.

Saturday brought three events. First up was the string quartet, Quatuor Diotima. My memory for specifics isn't good enough to give any real assessment, but each of the four works had at least a few charms: Thomas Simaku's "String Quartet No. 5" (2015) and Dieter Ammann's "String Quartet No. 2 'Distanzequartett'" (2009) I recall as being enjoyable enough (sleep deprivation beginning to assert itself once again). Heinz Holliger's "String Quartet No 2" (2007) was also fascinating, resolutely "old school" in some respects but entirely solid and imaginative, ending with an extremely effective last seven or eight minutes worth of the players humming along with their strings, really strong. Here's a version by the Zehetmair Quartet.

In the early evening, Apartment House (Gordon Mackay, violin; Hilary Stuart, violin; Bridget Carey, viola; Lukoszevieze, cello; Thomas, electric keyboard; Simon Limbrick, percussion) put together an imaginative program of seven pieces, beginning with a wry one from George Brecht, "String Quartet", which consisted of the four string players shaking hands politely. :-) This led to an enjoyable string quartet by Toshi Ichiyanagi followed by a hazy sextet work form Jon Gibson, "Melody IV Part I" (1977). More to my interest was Peter Garland's "Where Beautiful Feathers Abound", a delightful collage of seeming (Native) Americana, very much an outlier and a fine one. An ok Christopher Fox work, "BLANK" was followed by an intriguing one credited to Louise Bourgeois, "Insomnia Drawing". Now I know that drawings within that category exist but I have no source listing her as a composer, so my guess is one of her drawings served as the score, but I'm not certain. In any event, it was a nicely shaky set of lines, indeterminate and blurry, something I'd like to hear again. Finally, the sextet performed Cage's "Hymnkus" (1986), a piece I don't believe I've heard before and a very fascinating one. Having since read a description, I get more of an idea about its structure, but its odd, blocky sense of repetition, never quite regular at all but having some overall sense of semi-transparent self-similarity, remains enticingly obscure.

The one set during the weekend that I didn't think worked well at all was the Berlin Splitter Orchestra later that evening. It was broadcast live on BBC and a pre-concert interview with Robin Hayward and Anthea Caddy indicated much discussion and planning for the event. It was inside a large older structure still in use as a mill, the seats and musicians (some 24 of the latter) spread throughout the capacious room. But apart from a staggered entrance of various groupings and perhaps some "rules" regarding iteration of sounds, I couldn't really discern much to distinguish the resultant music from what often happens when large bunches of improvisers get together, which is to say, not much. Granted, I stayed put at one end of the festivities, in close proximity to Andrea Neumann, a young trombonist and a drummer, within easy hearing distance of an electronicist, bassist Clayton Thomas and Hayward, but I could still make out much of what else was occurring in the room, notably contributions from Burkhard Beins and (I couldn't see them) either/both trumpeters Axel Dörner and Liz Albee. There were many fine musicians present--apart from the above, Kai Fagaschinski, Sabine Vogel, Ignaz Schick, Boris Baltschun and others--but for me, things never gelled. I could easily have been missing something.

Noontime Sunday allowed me to experience the Arditti Quartet for the first time, though I've little real idea how the ensemble has changed over the years, violinist and founder Irvine Arditti being its only original member. Two of the four pieces I found entirely competent but more or less forgettable, John Zorn's "The Remedy of Fortune" and festival stalwart Harrison Birtwhistle's "String Quartet No. 3: The Silk House Sequences"--more technical flash than substance to these ears, though bearing craftsmanlike elegance. A nice surprise, though, was Iris ter Schiphorst's "Aus Liebe", especially its first half which featured some astonishingly moving writing for viola. I don't think I've heard her work before and need to fix that post haste. But the real stunner was Klaus Lang's "Seven Views of White" a 40-minute study of restrained tension, minutely variable lines relayed from instrument to instrument, needing to be handled with supreme delicacy while also imparting tensile strength, like stretching filaments of grainy gauze. Outstanding work, breathtakingly performed.

In the late afternoon, I attended a talk by David Toop. Speaking with him the day before, he hadn't quite decided on his approach to the subject, AMM. I understand that, in recent years, he;s tended toward not doing "lectures", instead presenting small environments of a personal nature. Here, armed with computer and turntable, original vinyl copies of "AMMMusic" and "The Crypt" leaned against the front table legs, he recounted his early experience with AMM, whom he first heard in 1966, often doing so over portions of music from those recordings. He was visibly moved at a few points, acknowledging how important this music had been to his development (and not just of a musical nature). Some attendees expressed skepticism about the personal nature of his recollections, preferring a more distanced approach but I found it to be a very welcome and warm way of explaining to the audience, a decent portion of whom were students, the context of the times and how AMM's stance could so deeply inspire the 17-year old Toop. I enjoyed it enormously and learned a fair bit in the bargain.

Finally, the first performance of trio AMM in about twelve years. I know there was some tense going early on in the circumstances revolving around the arrangement of this event but, as said above, any fears as regards untoward tensions had evaporated in the previous two days, so I went into the concert hall quite relaxed. As an AMM set goes, it was perfectly satisfactory if hardly transcendent. FOr the vast majority of its duration, the music remained very quiet, the most notable disturbances being a violently upthrust keyboard cover on the part of Tilbury (very effective when it occurred) and a world record Longest Sustained Cough by an Audience Member (although there were a few pretenders to the throne as well over the course of the concert). As a whole, it was fairly steady-state, none of that "AMM arc". Prévost was predominantly doing bowed cymbals and metals, with great sensitivity, enough that some members who don't normally care for that avenue weren't too upset. Me, I thought fared very well, gradually honing his attack until a sublime moment when, holding a cymbal by its stand (a small sock cymbal, maybe?) over the snare, he bowed it and very lightly allowed it to touch the top of the drum, resulting in an exquisite buzz. Rowe intentionally limited his palette to three or four sounds, most of which resembled what's been heard in his recent Twombly-esque period (sans any classical samples) but also, in a historical reference to AMM, brought out his radio which had been MIA for a while. His most striking contribution occurred toward the end when he picked up a pop song, allowed it to linger around longer than usual and then let a second one appear, this bearing lyrics that referred to "yesterdays" and suchlike (I wish I could recall more specifics). Perhaps due to that, he let it remain for four or five minutes, really pushing things, drawing a quizzical glance or two from Prévost. But if I had to pick a highlight, it was Tilbury, particularly his kneading, even caressing of the piano. Kjell told me later he's been doing this lately (though he hadn't when I saw him in Paris). It takes several forms. One involves laying his hands flat on the keys, exerting extreme tension between upward and downward movement, eventually, just barely depressing a key or two, sometimes resulting in a sound, sometimes not. It was so gripping. More, we would caress the body of the instrument, rubbing his hands along the keyboard cover, underneath the keys, on the sideboards, very much as a lover. One couldn't help but think of his age (79), his relationship with the piano, his corporeal love for the instrument. So intimate, so moving.

A great three days, not only the fine music but all the warm and deep talk and camaraderie. Thanks to everyone involved.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)